On a hot summer afternoon in July 2023, a saw-scaled viper (a species of snakes) stung 12-year-old Nandita in Maharashtra’s Kolhapur region. After the panicking family reached the Asha worker Archana’s home, she immediately opened up an application on her mobile phone and started following the instructions accordingly till the vehicle arrived to admit Nandita to the hospital.

Archana learnt using the application ‘The Snakebite Assistant’ in a community workshop held in 2022. The application developed by Snakebite Healing and Education Society (SHE-INDIA) has 10K+ downloads. It works on the principle of offering guidance to victims and first responders to prevent snakebites and to respond appropriately at 3 levels: Paramedics, health centres and district hospitals.

“Earlier, the immediate response to a snakebite often involved taking the patient to a faith healer or hospital. However, the critical first few hours post-bite can determine the outcome between life and death. The app provides clear and efficient instructions for administering first aid, significantly enhancing the chances of survival and minimizing potential complications,” Archana told Mojo Story.

The app provides a comprehensive list of updated training material divided according to the stratified knowledge of the user and links to educational material for individuals, communities, and schools.

“Initially, when we used to go to the villages ourselves and conduct the training session. But later we realised the better way to spread awareness is to conduct the capacity building workshops amongst Zila Parishad, Asha workers or Sarpanch who are well-connected with the locals,” said, Priyanka Kadam, founder of SHE-India.

India’s snakebite problem

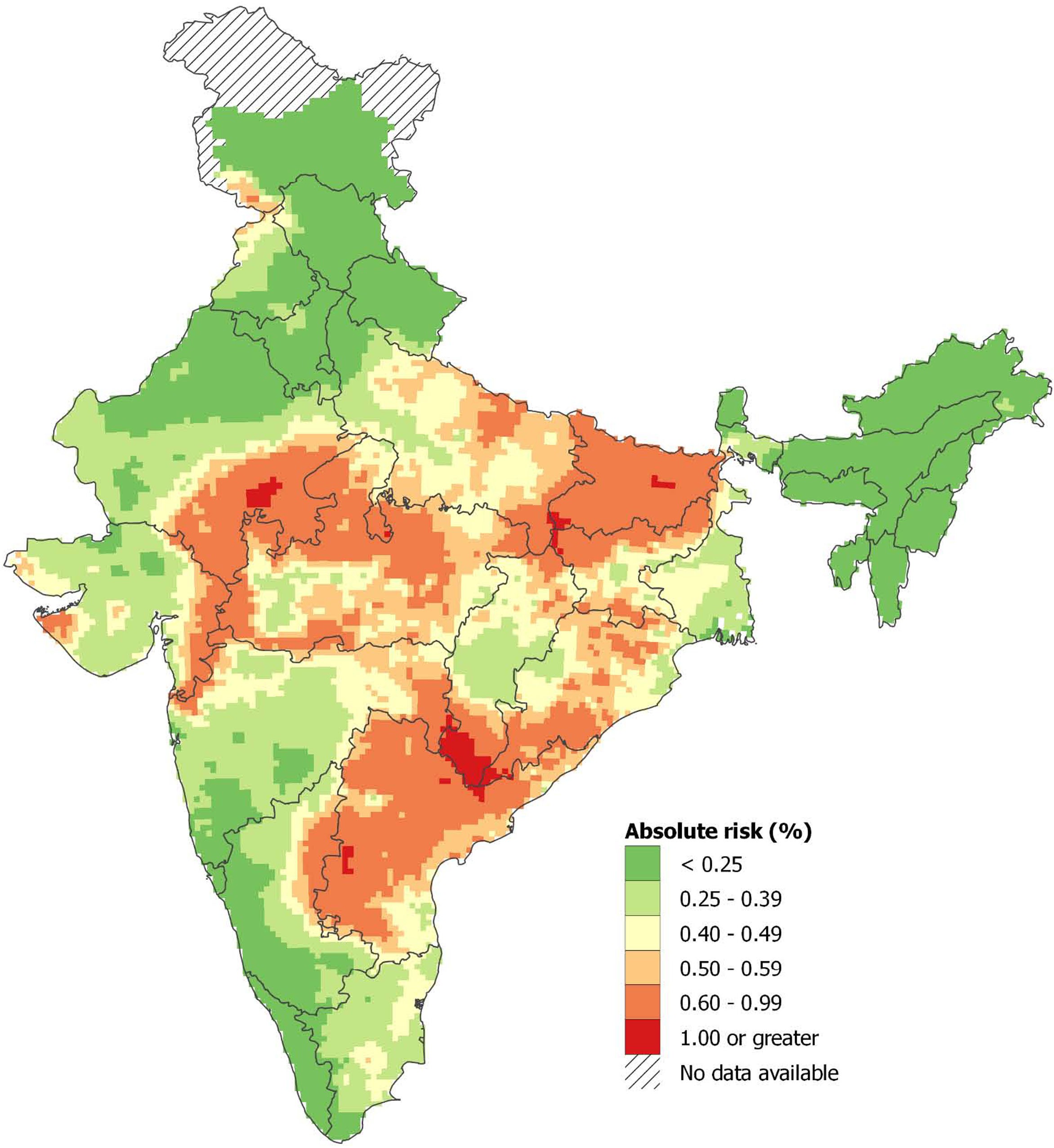

India remains the nation most severely impacted by snake bite incidents, with an annual average of 58,000 fatalities, comprising over half of the global total of 81,000 –138,000 deaths. In 2020, a comprehensive study was conducted in eight states—Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, the combined region of Andhra Pradesh (including Telangana), Rajasthan, and Gujarat— and was concluded that they bear the greatest burden of snakebite fatalities, contributing to over 70% of deaths from 2001 to 2014.

In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) designated snakebite as a neglected tropical disease. Subsequently, in 2019, it established a goal to reduce the global impact of snakebite by 50% by the year 2030.

“It is a nice guide for the young medical professionals to take all the observations, assessing the parameters, to ascertain whether the person is envenomed or not… The apps are a good tool for researchers to conduct extensive studies other than the general public,” said Kadam.

Instant Information

In recent years, there has been a proliferation of various applications akin to Snakebite Assistants, each serving distinct purposes such as delivering informative content, curating databases of snake species, and aiding in locating hospitals equipped to handle snakebite emergencies. This diverse array of apps including SARPA (Snake Awareness, Rescue and Protection app), Serpent, Snakepedia, Indian Snakes, Snake Helpline, among others.underscores the expanding ecosystem dedicated to addressing snake-related concerns and enhancing public safety.

Arun Nair, a 21-year-old young medical professional student in Kerala, has been using the Snakepedia app for his research work. The app has a comprehensive database of snake species along with a gallery of HD photographs, expert online help for identification, and contact details for rescuers and hospitals with anti-venom. Users can access articles on first aid, ID tips, and podcasts, alongside busting myths and facts.

“With the information and knowledge I learnt from the app, I have been able to help a lot of people in my village in case of emergencies. Previously, panic often led people to kill non-venomous snakes. However, now with knowledge about over 300-400 snake species, their traits, and habitats, I can now take appropriate actions to address such situations effectively,” Nair told Mojo Story.

In India, the longstanding issue of underreporting and insufficient treatment of snakebites in India due to low literacy rates and a lack of knowledge on proper handling. In rural areas throughout India, the reliance on traditional faith healers like ojhas and gunils for medical treatment persists. This preference stems from limited access to healthcare facilities and the financial burden associated with medical services, even where available.

Nair emphasized that the snakebite apps are playing a crucial role in addressing this challenge, indicating a positive shift in awareness and response. “The doctor in the hospital can turn away a person but faith healer will always accommodate you. It is more about the trust factor. But slowly, things are changing,” he added.

Apprehensions about the apps

While the mobile apps claim to solve the snakebite problem, Jose Louise who launched Indiansnakes.org, and subsequently the Serpent app, has a few apprehensions about this.

Speaking with Mojo Story, he said, “The mobile apps are just like any other tools to find the nearest hospital and also give some awareness and education to the end user like what snake is venomous what is non venomous along with some do's and don'ts. The apps cannot provide treatment.”

He added that the mobile application Serpent was used by a lot of people in this country to find the nearest hospital. “We made a database of hospital and put it in the mobile application. So, that in case of an emergency, you can find the nearest hospital,” Louise told Mojo Story

Louise added that the procedures to be followed in case of snakebite change from case to case depending on how much venom is gone inside, what species and what part of the body is bitten depending upon the time to taken from the snake bite to the treatment.

Advising against the mobile app based treatment of snakebite, he said, “In a country like India, looking at a mobile phone and following up treatment is not advisable. Mobile applications should not be giving the treatment protocols or methodology. They should be a reference place, or a useful tool, to identify snake species whether it is venomous or venomous.”